by Airan Wright

View Article

Cognizant Softvision (Originally published July 20, 2018 at Magenic Technologies)

We all love a good story. A fellowship of travelers on a quest to destroy a magic ring. The hasty judgements and emotional reconciliations of Georgian-era English gentility. An NYPD detective coming to terms with his estranged wife while rescuing hostages from Russian terrorists. The act of taking a journey through mentally and physically challenging terrain, of coming face-to-face with adversity and accomplishing a resolution, yields a cathartic release and reminds us of our own humanity.

But why do stories have so much power over us? What is a story, exactly? What are its parts?

THE HERO’S JOURNEY

Writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell tackled these questions by boiling down all narratives to a collection of elementary ideas. His “monomyth” theory summarized his effort by putting forward the idea that all stories can be defined in a singular, universal way. More specifically, Campbell looked to define the central working parts of what a story is, regardless of what local or folk interpretations could be added to make it pertinent to a specific audience. In the introduction to his book of collected works entitled “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”, Campbell writes: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered, and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on their fellow people.”

This is the “hero’s journey” in three acts: the departure, the initiation, and the return. Several variant actions may happen within each act, but they all support this recurring tenet of a journey with a beginning, middle, and end.

CIRCULAR STORIES

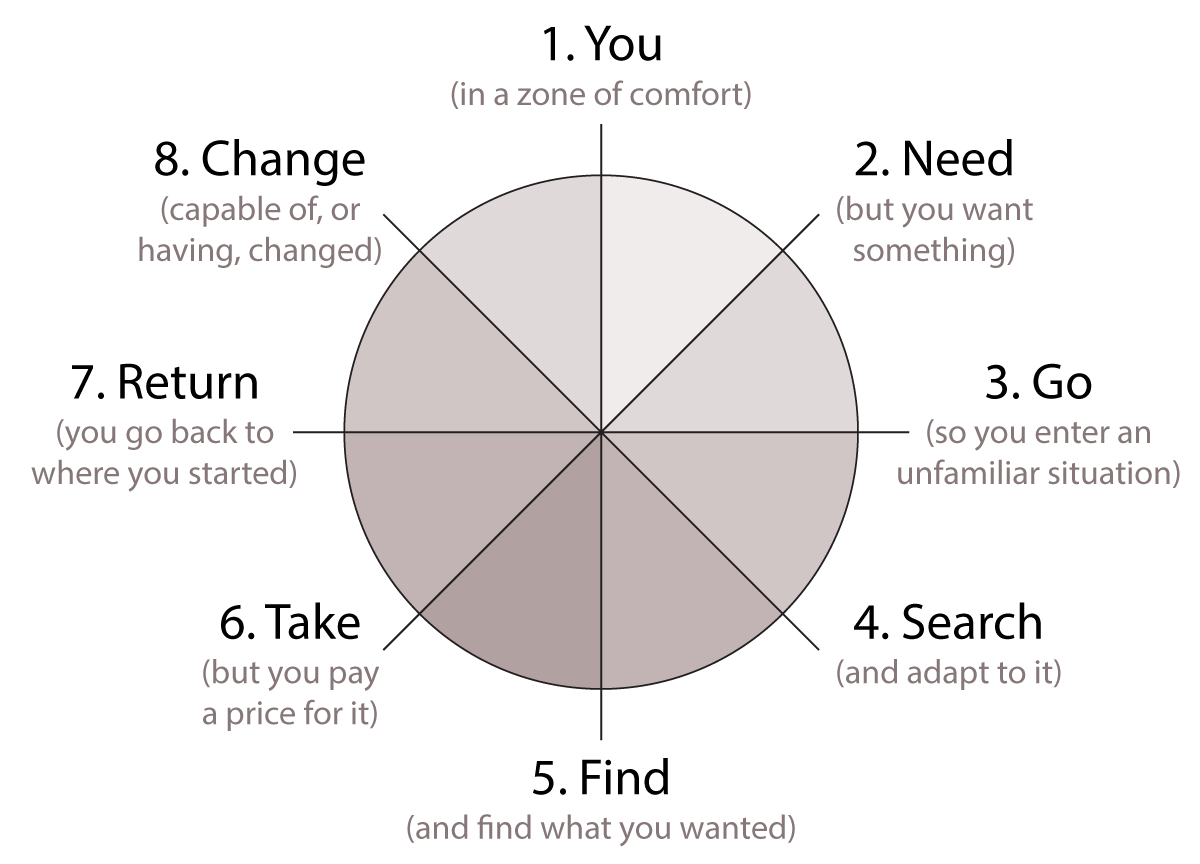

Dan Harmon, creator and writer of the shows Community and Rick and Morty, further helped define this journey by way of a circular story approach, whereby the hero…

- Starts in a zone of comfort.

- Traverses around the circle wanting something.

- Enters an unfamiliar situation to get it.

- Adapts to the new instance.

- Finally gets what they want.

They then venture up the other side of the circle by way of…

- Paying a price for their success

- Returning to their previously familiar situation

- Having changed.

At this point the hero can start again, over and over, for as long as there is conflict and resolution. Readers experience a hero’s story in this way, becoming invested in their desires and faults, growing with them as they pay the appropriate price, and celebrating their return to normalcy as a better person for having dealt with adversity. We collectively breathe a sigh of relief—our catharsis complete.

This approach makes for good storytelling, as has been proven countlessly time and time again. But does it have real world application beyond the covers of a book? Can understanding story structure help us in everyday life? After all, it’s one thing to lose one’s self in a mythical story. It’s an entirely different thing all together to say, clean the bathroom or pay the bills or go grocery shopping. Or, to put it another way, to test a bug, develop a sales plan, or write code.

Maybe it isn’t all that different, though. “Experience” in the simplest sense can be defined as the “direct observation of or participation in events as a basis of knowledge”. (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/experience) We are all aware that events have a definite beginning, middle, and end and, as we discussed above, stories are no different. Events are simply stories where the subject is less the culmination of a series of cleverly worded descriptions and more the actions of a real person. In a very real sense, an event is simply a (auto)biographical story. It is the story of a user’s experience through the participation of an event…an event that can be thought through and designed to give the user the best story possible.

UX DESIGN DECONSTRUCTED

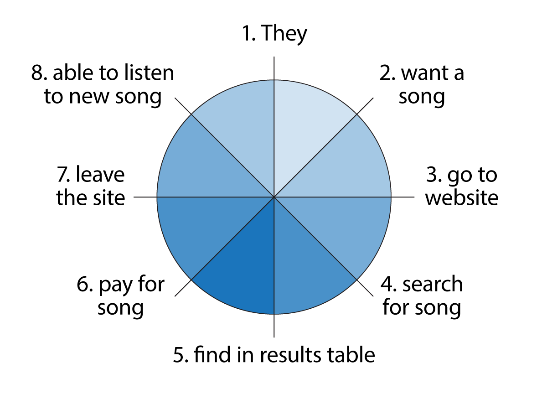

A user’s experience is, at its simplest iteration, a basic story structure. A user wants or needs something from an application, journeys into the software to find and retrieve their goal, and returns having paid the price for their actions. This “need” could be any number of things…a phone number, dinner, a song…it doesn’t matter what the user needs specifically. It only matters in so much as the user needs a thing and must travel into the application to get it.

Take for instance a user’s desire to purchase a favorite song. We might assume they (1) want a song (2) so they go a website (3). They look for tools with which to search for their desired song (4), finding it in a search results table (5) and pay for it (6). They retrieve the file from a download button or email and leave the site (7) returning to their computer to play their newly acquired purchase (8). As a UX Designer, we can’t do much about steps 1-3…that’s up to the user. Nor do we really care about steps 7-8 (unless we are also the manufacturer of the device that ends up playing the music).

Steps 4, 5, and 6 are something we can work with though.

In step 4, the user “searches” for an item. UX design frequently must find a natural and easy placement for searching. In recent years, this has added Voice User Interfaces (VUI) through the introduction of chatbots like Alexa and Siri. Placing search functionality into a site should never be an afterthought and, one could argue, is possibly the most important action you can build into a site. This can be either in the form of active searching via a text entry field or passive searching via easily identifiable visual cues on the page. For instance, a passive approach to providing contact information might be via the footer of a site where it is very common to place a phone number or address. Contemplating better and quicker ways for the typical user to find data increases the likelihood that they will return in the future and builds trust between the user and the site.

Similarly, step 5 also offers an opportunity to build trust. When a user sees their “found” data for the first time, is it filterable? Can we sort it? Can we refine our search? Can we configure our results table to show what we find the most useful and save that configuration for return visits? How quickly can results be returned and can they be stored or shared? All these questions will likely have different answers based on what the client provides the user as a service, but they are all universal in their need to provide a user the ability to sift through found data in a way that allows their desired content to float to the top.

And finally, in step 6 the user is asked to pay for their resulting data in some way. That can look like a wide variety of things…but in this step we can affect real change. Take for example the purchasing of a song online. We may consider the payment of funds for a song to be what step 6 embodies, but it’s also much more. It’s wrapped up in how much time it took to complete the process. Was their value added with similar song recommendations that didn’t get in the way of the main goal of purchasing the searched for song? Were items placed on the page in a way that was the least confusing possible so that the user didn’t have to work as hard? Payment in this case then takes on new meaning. For a successful UX experience, we ultimately are trying to eliminate as many pain points as possible to give the user more bang for their buck.

If you are asking yourself why this seems so obvious, it’s because we, as a society, have come to much more value time as a commodity and are critical of those actions that waste it. Therefor a successful user experience is highly associated with the lack of perceived wasted time.

THE ADDED BENEFIT OF SUCCESS

Additionally, our understanding the methodology behind why we should make an experience match a good circular story structure allows us to actively build thought provoking narratives that give a user more investment over time. With more investment comes a better chance of creating a product advocate. It’s not so dissimilar to the approach streaming serial television has been enjoying for the better part of half a decade. When we watch a good story on tv, the first thing we want to do is share that excitement with others. Good UX should aspire to do the same.

For example, understanding the high likelihood that a user will search out contact information on a site means we have opportunities to help adjust the “search”, “find”, and “pay” steps so as to build user confidence that they are being heard and cared for. Taking steps to make contact info one click away for instance. Or by giving a map to a physical location and asking if the user would like those directions sent to their phone. When we lower the amount a user must “pay” by eliminating time spent searching for, finding, and getting directions to a place, we create opportunities for the user to become an advocate.

Tools for lowering the pain points of a site could include contextual menus, augmented reality integration, or voice user interfaces (VUI). At the end of the day though, really anything that helps a user “pay” less in time and effort during the “search” and “find” steps help to build trust and confidence. These are the interactions that keep a person returning to a site.

IN CONCLUSION

Campbell states in Pathways to Bliss: Mythology and Personal Transformation:

“Artists are magical elfs. Evoking symbols and motifs that connect us to our deeper selves, they can help us along the heroic journey of our own lives. […]

The artist is meant to put the objects of this world together in such a way that through them you will experience that light, that radiance which is the light of our consciousness and which all things both hide and, when properly looked upon, reveal. The hero journey is one of the universal patterns through which that radiance shows brightly.”

As UX designers, we assume that our users are taking a journey and that the vehicle or world we are applying our actions to is a piece of software. We make the logical assumption that our user comes to the application with a need, takes steps to satisfy that need, and leaves hopefully having been successful to some degree. Their story has a beginning, a middle, and an end that is up to us to mold into a gratifying experience.

But is the end ever really the end? In a much larger picture, our user’s successful journey merely starts another more important journey: that of the advocate. Someone who sees the value in the story to such an extent that they share it with others and, in doing so, grow an audience. Even here, the circular story continues: a user sees a need to tell others about a pleasing experience, they search for a new audience, they share their experience with them, and leave having imparted information on new ears.

The end of one story is the start of another.

—