by Airan Wright, 4/1/22

(Purchase / listen to the album here)

The maxim “I think, therefore I am” is a curious one. René Descartes’ philosophy, taken at face value, simply states that you exist because you think you do. But, in another sense, it asks you to contemplate an existence where you are at the center, a singular individual sentience with the ability to experience feelings and sensations, responsible for the creation of everything you see at any given moment. That you are creating your entire universe haphazardly, improvising every detailed object in the moment simply because you think of it. And, with no way to prove that every person you meet isn’t a self-created form molded from your thoughts, it’s technically a plausible answer. That is, until you step back and reveal some of the flaws in that logic.

To start, humans tend to be a social collective and, when put in isolation from one another, we are subject to breakdowns in mental and physical health. Look at the first two years of this pandemic as evidence. Furthermore, given that self-preservation is typically a priority for all living things, it seems highly unlikely that an individual sentience would voluntarily build into its process bad health as a sort of self-sabotage. Secondly, we are faced with the thought of nonexistence daily. Threatened by it. Afraid of it, in fact. Again, though, self-preservation is a strong and compelling force. The possibility that nonexistence or, more colloquially, death is a construct of an individual sentience is hard to believe. Why build such a complex and visually mesmerizing world only to create a way for it to be arbitrarily removed from your existence?

Obviously, we can’t prove anything about the nature of existence without a shadow of a doubt. That’s the problem with “I think, therefore I am.” But maybe we don’t have to. Maybe we can put our trust in Occam’s razor and believe in the simplest answer: that there is more than sentience in the world because for there not to be means believing that those things that cause pain and death are simply there on a whim. That death defines life provides support for the all but proven fact we are not simply the random construct of a single consciousness.

Which highlights a very specific dilemma: If we are a collection of individuals capable of seeing the nature of existence through separate sets of eyes, how do we know that what one person sees is the same as the next? We are each at the center of our own tiny universe, drifting about a plane of existence and interacting with each other, entangling our spiral arms full of galaxies and pushing and pulling with our gravitational influence upon one another. What is the mechanism for relating what we see and feel and hear to each other?

The answer is that only through a combination of facts and emotion, using numbers and data to construct a scaffolding on which we hang emotionally charged wavelengths and textures can we develop a shared understanding. Such is the nature of the world: a combination of scientific brilliance and emotional beauty. This is art.

1. The Language of Art

Ask a hundred people to define “art” and you are likely to get a hundred different answers. That makes sense. Art can mean a lot of different things. It can be the definition of color on a medium. It can be a scientific algorithm dictating the placement of leaves on a stem. It can be the dissociation of a sweet smell with a bitter taste. It is sensual and warm, yet crisp and cool. Oddly specific and entirely vague. The power of art is in our ability to use it as a form of individual interpretation of our universe as we individually see it, putting down our unique view of it for others to digest.

However, art isn’t a perfect language. To someone who is colorblind, the variations in wavelength distributed to their eyes from a painting rich in color may appear muted, causing focus to be cast instead upon shapes and texture. To the musician suffering from years of hearing loss, the richness and dynamic vastness of a string orchestra might switch focus from tonal color to intricacy of note choice. Even two people of roughly similar biological makeup will experience shifts in the goal of a piece of art, depending on their social status, health, or past experiences.

Because of these discrepancies, the only way to truly get a sense of what a piece of art really “means” societally and historically is through the amassing of statistical data. By presenting art as the artist intends and polling the public on their perception, the significance of a piece can grow or shrink, fading into nothing or remaining a shining example of a given age. In a purely mathematical sense, this is a scatter plot, where the general consensus of a piece dictates its long-term meaning, whether or not that matches the original artistic intent. And it can shift, favoring this or that opinion over time.

Art that lasts thousands of years is protected from obscurity by these points on a graph and, as the data points grow, the message becomes more generalized until something created out of extreme strife and anger can become trivialized and banal thousands of years later. This is the power of “error cancellation.” It is the act of collecting a huge data sample and taking the median output. “Errors,” or “outliers,” of both the positive and negative, blended into the background, leaving the general idea or concept of what was meant as a guidepost for others.

In this sense, error cancellation sounds oppressive, but in truth it can also be a very useful tool.

2. A Study in Error Cancellation

Creating art is a Pandora’s box, for once you start you can’t stop. You immediately see how your art as an expression of yourself is a way in which you can speak your truths to the world. It is a freedom of expression that is all your own. But, try as you might, your first attempts are frequently not what you had in mind. This is to be expected. It takes trying again and again, every so often glimpsing what you want to say captured in a piece just so, to create an artistic voice. This is the basis of practice: that, by slow and steady repetition you create a “look,” folding in errors (if you can really ever call them errors) as points of experience. Much like a scatter plot, the more data you create and the more art you give life to, the more defined your artistic voice becomes.

This album, for me, is a very small study of this phenomena. It is the idea that a solo voice can attempt to tell a story, slipping on details and getting things sort of right, but also sort of wrong until a second voice steps in and provides support. That a third and fourth voice can further define the story, taking a note and adding another until an hour later the track has settled aurally into a vi(add9) or ii7b5 or V7 chord. Or that played with the right tonalities, a tone cluster of low D, D#, and E might sound beautiful and dark together where a high D and D# simply did not.

Or, to step sideways a little, that a splatter of black paint might look out of place, but layered under splatters of red, yellow, and white, the ensuing texture becomes less dissonant and more harmonious. That a dash of cumin might be jarring unless it is combined with salt and chili powder. The single voice walks an uneasy tightrope that is unforgiving, showcasing every bobble and slip, but each new addition strengthens the discourse, allowing for a more confident voice to be heard.

3. The Challenge of Art in Isolation

As Covid-19 hijacked our lives, relegating us to isolation and dictating that our social interaction be through a tiny digital window, I think it’s safe to say that artistic output ground to a halt. Undeterred, we found a way to make it work though, switching gears to recording from home, creating online galleries, streaming live solo concerts with virtual tip jars, and creating audiovisual pieces to replace our gigs. Gone for a time was the ability to play live music with others, voicing thoughts on the fly and having other musicians reply in turn.

But, to use the old adage “the devil is in the details,” recording one’s self at home shines a very bright light on what a single voice sounds like all alone. For anyone who had recorded in a studio before the pandemic, this sensation was not entirely new. Playing in an isolation booth is a singularly humiliating experience. Every small chip in your sound and every pitch correction placed a millisecond after your entrance can be heard in great detail on an isolated track. Your misplaced breaths, the keys clacking, and the air escaping through the corners of your mouth when you are tired…things that would be forgotten or never heard in the first place when played live are excruciatingly there for all eternity when you review it in a 32bit, 48 kHz waveform. On top of that is the addition of a visual component which, for many, was simply getting into a suit or tux and showing up at a venue.

At first glance, the idea of recording from home sounds great. Who wouldn’t want to cut out travel time to gigs and wearing dress shoes (or pants?). But the truth of the matter is that recording from home is almost more work. Practicing parts even more than you used to since you can’t simply punch in on video without being incredibly obvious, getting dressed up, picking a backdrop, and “acting” while playing perfectly…it’s hard work. Even professional session players in studios know that what looks like a 5-minute piece can take an hour in some situations. With the air conditioner randomly turning on and the baby crying and the car alarm going off, five minutes can quickly turn into a night of work. This is the beauty of error cancellation as a concept and in practice. Understanding what will or won’t be heard in the final mix is a skill that comes with practice. After 30 tracks are in a piece plus reverb and mastering, will the air conditioner ever be heard? Eh…maybe. Will it affect the track? Probably not. Will the casual listener who is tuning in to a compressed digital file ever hear the nuanced fade you put in the silence of the track to remove it? Almost certainly not. This is not to say that you shouldn’t finesse your art. By all means, do so if you have the time and energy. Rather, it’s to point out that the sooner you can live with outliers in your process, understanding them for what they are, the faster you’ll be at creating your vision and, ultimately, the more fun you’ll have. Finishing projects is just as important as starting them, and it is all too easy to start something that will take months to finish…and then never finish.

4. Producing Content Is Hard Work

When faced with an audience that is captive, stuck inside a home and unable to go out, new content becomes incredibly valuable. However, it should come as no surprise that producing content is hard work. For a month or so, it might be okay to simply stand in front of a camera and play, but attention spans are a fickle thing. Eventually, you have to up your game and add visual content. For a 5-minute music video, an artist is likely doing many or all of these steps:

Audio

- Composing a piece (written or improvised)

- Creating a MIDI click track and/or videotaped conductor track

- Booking additional musicians as needed

- Recording (or soliciting recordings)

- Mixing

- Mastering

Visuals

- Ask musicians (including self) to send video with their audio submissions

- AND/OR insert video project here (time lapse art, animation, short film, etc.)

- If creating this piece from scratch, add additional visual art time for any and all work required, including storyboards, sketches, filming, etc.

Post-Production

- Sync audio to video clips

- Pre-comp any complex collaborations for better computer processing (unless you are lucky and own a video editing suite and suitable computing power)

- Draft render of video for spot check

- Revisions and re-render (if needed)

- Final render (in multiple formats depending on desired release location)

- Release

- Collect musician info for tags

- Write content for media descriptions and posts

- Decide which platforms to post to

- Promote on social media

- Ask your audience to follow you

Repeat

In order to move forward, making this process repeatable and fun, the game becomes a balancing act between perfect vs. useful. In short, if you wait for every step to be perfect, you will never get to the end of the project. You have to trust that little problems will normalize over time. To borrow from the novel Don Quixote by the esteemed Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, “it all comes out in the wash.” Things have to be just good enough for you to progress to the next step, allowing for error cancellation to fold in the pieces that might look odd or out of place and allowing for the sum of the whole to be greater than its parts.

5. Art on Hard Mode

None of this is to say that art can’t or shouldn’t be challenging. There certainly is a time and place for art that requires significant skill to create with any sort of nuance: black and white photography, ink sketches without pencil, solo repertoire for any instrument, knitting complex projects without a pattern, or freestyle hip hop. This doesn’t devalue excellent art that took time to practice and create and can shine in its singular voice, flying high above the ground without a safety net. And yet, it’s really still the same path as before. There are still errors…they are just harder to see. There is still that whittling down of what defines one’s artistic voice…it just took years of practice behind the scenes. “Art on hard mode” takes more time and, as we are all familiar, time is an expense we choose to pay for a desired outcome.

There is an age-old Venn diagram that spells out the relationship of Quality / Quantity / Time that is applicable here. In the grand scheme of things, the “art on hard mode” artist will almost always end up sacrificing Quantity and Time for Quality. Even someone like Mozart who, if the mythologies are correct, composed whole works seemingly overnight, couldn’t see them to fruition without having an orchestra to rehearse and perform with. Or having a patron to fund it. Mozart, as amazing as he was, still fits within this paradigm, sacrificing Quantity and Time for a dot on the Venn diagram squarely in Quality.

Indeed, most “finished art” falls into this same category. A single finished painting, researched and planned for, takes a long time to create. A solo recital takes months of practice, all for one performance. Comparatively, dropping the quality or time of a project can lead to faster delivery but at a cost. Take, for instance, twenty 3-minute sketches that are unplanned and free-form from memory or a sitting with a live model working on one piece over the same time frame. Or 5000 mass-produced postcards of a painting versus the original done in oil. 1000 CDs/LPs of a show or being at the concert, existing in the same space as the music being created.

Everything comes at a price. So, what is the price of this project? I would argue that, in the Quality / Quantity / Time diagram, the only way to hit a bull’s-eye is to be okay with “good enough.” To let things go and not fret about them. To let error cancellation allow for those elements you know to be disharmonious with the end goal fade into the mix without worrying about correcting them. Error cancellation, simply put, means the freedom to create art without the worry of perfection.

6. The Art of Letting Things Go

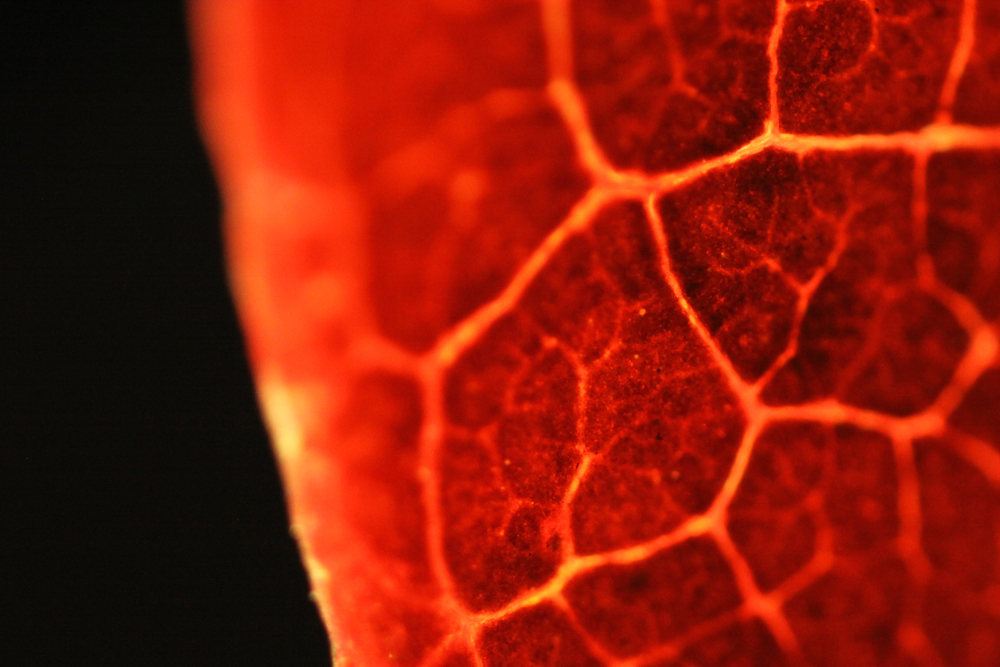

A study in error cancellation is a study looking at the value of the whole, not the pieces. I think this is why I love live music so much more than produced studio albums. Each note performed live is never “perfect” under a microscope, but all those errors…all those bobbles and wavers and bends…they blend together. They cancel the need to be perfect. In some respects, it’s perfect for not being perfect.

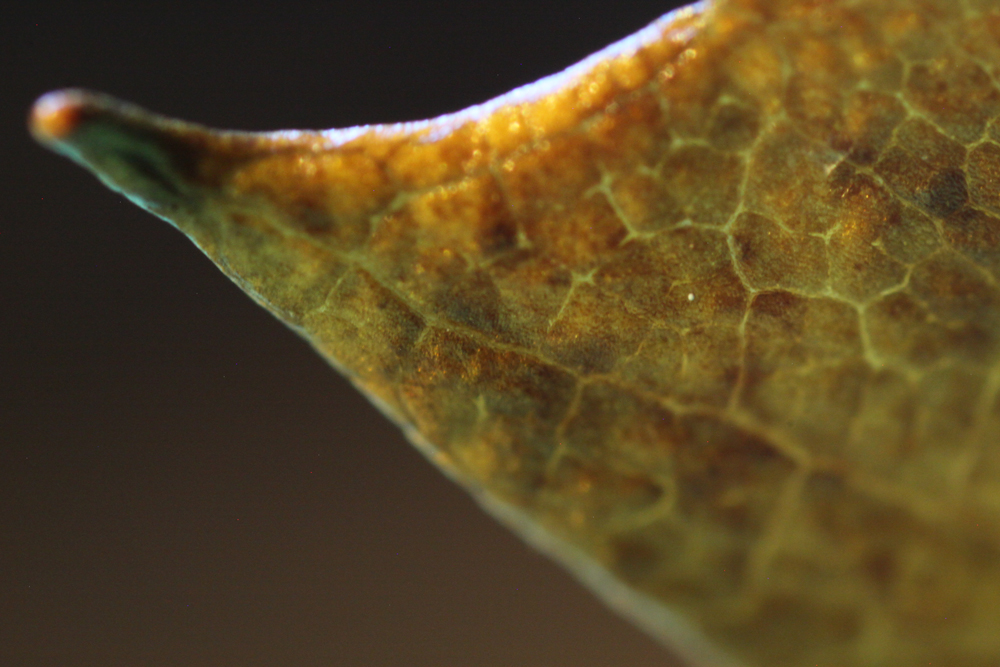

And, in a very literal sense, that’s what being human is. A culmination of variances in DNA and cell division that lead to a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts.

Extended isolation does one thing very well: It highlights everything you were before you were locked away and exposes it for your seemingly unending contemplation. Because you are no longer able to hide your mistakes in the comfort of a crowd, you see your hiccups and faltering as if it had all been amplified by a factor of a million. We are our own little universes in which our core being sits in the center. When we are social, our galactic arms touch and mix, and we lose a little of ourselves in the mix. We become something bigger. But take that away and our selfishness and our desire for self-preservation pull us back inward.

Remember…the devil is in the details. It’s easy to get stuck obsessing on the tiniest piece of a puzzle and forget the big picture. To look at the scale in the morning and feel guilty about having dessert the night before. To wonder if you said the wrong thing in a meeting because someone scowled, not knowing whether it really had anything to do with what you just discussed. To work over lunch because you can, instead of taking a moment for yourself.

Remember…it all comes out in the wash. When we are by ourselves, we hear every little mistake. Every waiver of pitch. Every misplaced breath. The things we catch are things we’d never hear in a group. But context is everything. Live for the bigger picture.

We are very good at letting details run our life. Error cancellation adds a buffer to that conversation. It lets you see your minor hiccups and misgivings as simple data points and not defining characteristics, accepting them without carrying the stress of them. We think, therefore we are: a collective of unique voices that, when combined on a global scale, paint a picture of beauty, recognizing outliers that give a voice to hate and discrimination as simple data points that ultimately will not define the whole.

–

(Purchase / listen to the album here)